Week 1: Introduction to Python

Basics

In this course we will be using the Python programming language. The material this week will help familiarize you with how to perform basic tasks in Python, as well as provide some context for why Python is a good programming language to learn.

Motivation: Why learn Python?

There are lots of programming languages, and lots of different things to invest your time in learning other than programming. So why is learning Python a worthwhile investment of your time?

-

With Python, there are no limits to the complexity of programs you can build. It’s no question that computers are becoming increasingly important in all walks of life. In addition to science applications, Python is used in building all sorts of software and apps, such as websites, games, graphical user interfaces (GUIs), business software, operating systems, etc. Examples of Python-built applications include Google’s search engine, Dropbox, and YouTube. There is nearly no limit to what you can design and build using Python, and it could become an invaluable tool in your future career. Even if you need to write components of your programs in a different language (such as a C library for a doing a certain type of computation efficiently), your Python program can easily communicate with it.

-

Python is a high-level language, which frees you from the more tedious and formal aspects of programming. In a lower-level programming language such as C, the programmer needs to interact more directly with the memory and operating system. Variables need to be declared and memory needs to be allocated before the variables can be used. In short, you need to invest a lot of time into the technical aspects of computer science before starting to do anything. With Python, programming is more intuitive because the technical “low-level” parts are automatically taken care of behind the scenes, and you are free to think about the “high-level” or conceptual aspects of your program.

-

Python is an interpreted language, and as such, there is no need to compile Python code to run it. When writing codes in C, Fortran or Java, a program called a compiler is needed to convert the source code into a runnable program. The program itself is comprised of instructions to the CPU and is generally not human-readable. On the other hand, for interpreted languages such as Python, the lines of code are read by a program called an interpreter which executes the code line by line (the Python executable and the Python interpreter are in fact the same thing). This model makes it easier for pieces of code to be shared and used rapidly, compared to compiled programs. All these small conveniences add up to rapid development of programs and applications.

-

Python has an extensive free software ecosystem. The Python open-source community has created thousands of free available packages (called libraries in other languages) that can be easily downloaded over the Internet and used in your own program. Many of these packages are available free of charge, including all the ones we are using in this course. Some packages provide new variable types that make it easy to deal with complex problems; for example, the

arrayclass in NumPy allows one to work with multidimensional arrays and matrices, similar to Matlab, and thedataframeclass in Pandas allows one to read, merge, and analyze data in tabular form, similar to Excel but with the automation capabilities of a programming language. Other packages provide new ways for you to use Python, such as thejupyternotebook that we use for all of our course exercises. There are also chemistry-specific Python packages that allow you to manipulate molecular structures and run simulations.

Why Python - a personal perspective from Lee-Ping Wang

Here's a bit of personal information about me, in case you're interested in knowing how I got into programming and why it's an interesting topic for me.

I first started using Python in grad school, where I was first introduced to theoretical and computational chemistry. During my undergrad research in a bioengineering lab, I had written some image recognition scripts using Matlab that determined cell counts and cell shapes from videos of blood samples taken under a microscope. (Prior to my undergrad Matlab experience, I had taken a C++ course in high school but I wasn't a very good student.)

I was surprised to find out how easily my Matlab experience transferred to Python. In particular, it was easy to use NumPy's arrays as a substitute for Matlab's matrices. I also found that it was easy to use Python to parse and modify files, as well as execute other programs automatically. These automation tools allowed me to efficiently carry out research tasks that would not have been possible otherwise, such as extracting thousands of structures from a simulation trajectory, running quantum chemistry calculations on each structure, and processing the results. I also learned numerical optimization in grad school and used Python to write a software package to improve the accuracy of force field models for proteins and other biomolecules.

In my postdoc, a large portion of my research involved Python programming and I published my force field optimization software "ForceBalance" and made it available to the scientific community. Over the years, ForceBalance and the force field models that were built with it gained traction due to the models' high accuracy and ease of reproducibility. More recently I also wrote a software package for geometry optimization that incorporates a lot of what I learned when writing ForceBalance. The new geometry optimization software "geomeTRIC" allowed me to implement and test a new coordinate system for optimizing the structures of molecules that enables calculations to converge more quickly and more reliably than before.

Overall, I think Python has become one of my most important research tools mainly for these reasons:

(1) Python makes it easy to implement mathematical formulas and apply them in practice, providing a bridge from "pen and paper" research to large scale computations.

(2) Python makes it easy to automate other programs, and enables the development of workflows and procedures that would be too complex if done manually.

(3) Python is widely used by the research community, making it easy for others to use and benefit from my research codes, and increasing my research impact in the process.

Why Python - a personal perspective from Kyle Crabtree

I was born at the right time for computers to be available in lower-middle class households when I was still a child, but before computers became so user-friendly that they could be used without knowing a bit about how they work. But although I learned how to navigate a DOS prompt (usually to load a video game) and dabbled with making HTML websites on the (now defunct) Geocities platform, I never touched real programming until after I started graduate school.

One of my first tasks in grad school was to build a device that could measure the diameter of a low-power infrared laser, which I presented at the International Symposium on Molecular Spectroscopy in 2008. After I built the device, I needed to analyze the data it produced. At first, I would download data from an oscilloscope onto a USB drive, then take the drive to a computer where I would load the data into a spreadsheet for manual analysis. Eventually, that got to be tedious, so I taught myself how to program in C (using the book C for Dummies) and LabWindows to create software that would read in the data from the device in real time and perform the analysis with a click of a button. This was my introduction to programming, and these days I use C++/Qt to write data acquisition software (Blackchirp) which is used to run chirped-pulse Fourier transform microwave spectrometers in various labs around the US.

C and C++ are both low-level programming languages, and although they are extremely fast and powerful, they are more cumbersome to work with than something like Python, which allows for faster prototyping and more flexibility when exploring data. In addition, the scientific libraries and data visualization tools available for Python have made it my choice for most data analysis. All of the students in my research group must learn how to use Python to analyze the custom data from our instruments, and we also use Python to chain together the outputs from more specialized software packages to automate larger analysis tasks. I've also used it to develop utilities which assist with common calculations for rotational spectroscopy which I make available to the community, such as my moment of inertia calculator.

While I will complain a lot about many aspects of Python, it is likely the language that provides the fastest and greatest return on investment: it is (relatively) easy to learn and use to build effective tools that solve problems.

Orienting yourself: Python interpreter, packages, environments

Note: This section will assume that you’ve already installed Miniconda and the environment following the Installation instructions. You may already have Python on your computer, but you will still need to follow the instructions to get your environment set up with all of the needed packages.

The basic Python interpreter is a program you can run by entering python in your Mac OS or Linux (or WSL) terminal.

The interpreter will give you an interactive >>> prompt, which understands Python commands such as print("Hello world!")

(base) leeping@desktop:~$ python

Python 3.9.13 | packaged by conda-forge | (main, May 27 2022, 16:56:21)

[GCC 10.3.0] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> print("Hello world!")

Hello world!

It is easy to get confused and type Python codes into the terminal without running the interpreter. Because the language of the terminal is bash (or another shell such as dash or zsh), not python, you will get an error message if you do this.

(base) leeping@desktop:~$ print("Hello world!")

-bash: syntax error near unexpected token `"Hello world!"'

The (base) part of your prompt is added by the conda package manager (which comes with Miniconda), and it shows that you are in the base environment, which is the default.

By setting the environment you are specifying a particular copy of the Python interpreter and a self-contained set of packages.

The ability to have separate environments is useful because there are multiple versions of Python and not all packages are mutually compatible.

As you learned in the Installation section, conda can create environments with different Python versions, and add packages into them while checking compatibility, but it doesn’t always work as smoothly as advertised.. 😤

Now activate the che155 environment, use cd to go into your designated CHE155 folder (optional, but recommended), and run jupyter lab as in the Installation instructions (bottom portion).

Click the link to open the Jupyter Lab environment.

From the Launcher you can open a new notebook with a single blank cell.

When changing to a directory with cd, are you typing in the Python language, the bash language, or something else?

Answer: cd is a bash command. However, many other commands such as listing directory contents (ls), copying files and directories (cp), deleting files and directories (rm) etc. are not bash commands but programs. When you type a command into the shell, it will look for a matching program in an ordered list of directories. This list of directories is given by an environment variable called PATH. You can see this environment variable by entering echo $PATH in your terminal. (echo is bash's version of Python's print.)

It is also possible to change directories from inside of Python using `os.chdir`, however, it is much less convenient. Therefore, it is better to be aware of the directory in which `jupyter lab` is being executed, so that the notebooks and other files you expect to be there are present.

The notebook is a system where you can enter lines or blocks of code into “cells”, and cells can be executed one at a time. The results of executing cells are stored in memory, so the results of each cell executation depends on the cells that have been executed before. This is a more convenient way of running Python interactively compared to using the console, for many reasons (for example, the console doesn’t give you an easy way to save codes).

Note: Another principal way of writing Python codes is to store them in text files.

These text files are called “scripts” if intended to be run directly, or “modules” if intended to be imported.

We won’t be writing many scripts in this course, but you’re welcome to explore programming this way; in fact the only way to share your codes with the community is by organizing your modules into packages.

When you use any Python module using the import statement, the underlying codes are all contained in modules that were installed by conda and live somewhere in the miniconda3 directory tree.

While scripts and modules contain only Python codes, notebooks also contain stored results and other metadata, so the Python interpreter cannot directly read notebooks.

So don’t try running a saved notebook as python my_notebook.ipynb or you will encounter all sorts of error messages.

Hello world: Print function, strings vs. variables

A classic (though possibly outdated) tradition is to have your first program print the string "Hello world!"

In your Jupyter notebook, enter the following code into a cell, then execute it to view the output.

print("Hello world!")

Syntax in Python is very important, just like any programming language.

Here we are calling the print function, and inside the parentheses are the argument(s) or input(s) to the function.

Also notice the quotes around "Hello world!", creating a string.

If the parentheses or the string hadn’t been there, you would have gotten error messages, for example:

>>> print "Hello world!"

File "<stdin>", line 1

print "Hello world!"

^

SyntaxError: Missing parentheses in call to 'print'. Did you mean print("Hello world!")?

This error message is actually pretty helpful, in part because it’s a very common error; in fact, this was how the print statement worked in Python 2, but in Python 3 this has been replaced with the print() function.

A different error message is given if the quotes are omitted:

>>> print(Hello)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

NameError: name 'Hello' is not defined

>>> print(Hello!)

File "<stdin>", line 1

print(Hello!)

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

>>> print(Hello world!)

File "<stdin>", line 1

print(Hello world!)

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

Without quotes, Hello and world are implied to be variables, but because the variable Hello has not been defined, attempting to print it produces an error.

Additionally, adding an exclamation mark after a variable has no meaning in Python, and neither does two variable names separated by a space.

You’ll also notice that the error types are different, where NameError indicates the syntax is correct, but the variable isn’t defined, whereas SyntaxError is printed when the code itself cannot be understood by the interpreter.

Even if this was overly simplistic, the take-home messages are:

print()is a function.- When calling a function, provide the arguments in parentheses.

"Hello world!"is a string.Hellois a variable, but currently not defined.Hello worldorHello world!are not correct syntax.

Assigning variables

There are many useful variable types in Python, such as string, int (integers), float (floating point numbers, the closest thing most programming languages have to true real numbers), list, tuple (read-only lists), dictionary, and numpy.array. A bool is a special kind of number that can only take on two values: True (1) or False (0).

All Python variables are also objects, which you will learn about later. To assign a variable, we enter something like this:

a = 3.0

where a is the variable name and 3.0 is the value.

(3.0 is an example of a literal, or a fixed value that is literally typed out.)

When assigning a variable, Python will automatically assign the variable type, which is different from many other programming languages like C or Fortran that require you to specify the type.

If the variable was previously defined, then the value will be overwritten by the assignment.

In certain cases it will be helpful to change the type of a variable.

There are special functions for this; for example, a = 3; b = float(a) will set b to a float with a value of 3.0.

You might have noticed that we actually created a new variable with the new type; we did not change the type of a in-place.

Operations

There are various ways to work with variables.

From a beginner’s perspective, one of the easiest ways is to use standard math operations +, -, *, / (add, subtract, multiply, divide).

In the expression c = a + b, a and b are called operands and + is called the operator; the result is assigned to c.

The result of these operations on numbers seems obvious from basic math, but it goes deeper than that.

A math equation is a statement that the left and right side are equal, and the equation is unchanged if the left and right side are swapped.

In Python programming, the line c = a + b assigns the value of c based on the result of the right hand side, even if c was previously undefined, and a + b = c has no meaning.

What’s more, the behavior of each operation depends on the variable types of the operands.

For example, adding or multiplying two ints results in an int, but adding or multiplying an int and a float results in a float.

The division of two ints also results in a float.

Things worked differently in Python 2, where the result of dividing two integers was another integer equal to the result of floating point division rounded down (in Python 3, that result is obtained using the // operator).

Two strings can be added resulting in a third string consisting of the two joined together.

Adding two lists also gives the same behavior, and that may be consistent with your intuition.

However, subtraction is not defined for two strings or two lists, and addition is not defined between a string and a list either.

A NumPy array defined using myArr = numpy.array([1, 2, 3]) might resemble a list defined as myList = [1, 2, 3], but the multiplication operations are defined differently.

Multiplying a NumPy array by an int or float results in each element being multiplied, whereas multiplication of a list by an int results in replicating the list multiple times (there is no definition of multiplying a list by a float).

The take-home message is that operations are more varied and complex than the corresponding basic math operations, and the result depends on the variable types of the operands (i.e. the variables being operated on).

While Python is often advertised as being an “intuitive” language, it actually depends on how well your own intuition lines up with the programmers that designed the language.

There are many other operations and I can’t give a complete list. For example, “modulo” a \% b means “the remainder of integer division of a by b”.

The power operation, i.e. “a raised to the power of b”, uses a double star: a ** b.

The operation > stands for “greater than”, and it returns True or False.

There are also >=, <, <=, == operations; == deserves special mention because it is used to check if two variables are equal.

All of these comparison operations return True or False, so they are very different from the assignment operation =.

There are other assignment operations as well. For example, a += b assigns a new value of a by adding the value of b to the original value. Other assignment operators include -=, *=, /=, which results in subtracting, multiplying, or dividing the LHS by the RHS, respectively.

# Some examples of operations on different variable types.

>>> 3*5

15 # Int

>>> 3*5.0

15.0 # Float

>>> 3/5

0.6 # Float

>>> "a" + "b"

'ab' # String

>>> [1, 2, 3] + ['4', 5.0, 6]

[1, 2, 3, '4', 5.0, 6] # Addition of lists

>>> "ab" - "a"

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for -: 'str' and 'str'

Functions

Functions, which have inputs (arguments) and outputs (return values), can perform more complex tasks than operations.

For example, there is no operation for the factorial: entering 10! will return a syntax error.

Fortunately, the factorial function has been defined in the SciPy package under the scipy.special module, so we can import and use it as follows.

Note: We don’t have a separate section on importing modules, but the recommended reading

[1] >>> from scipy import special

[2] >>> special.factorial(10)

3628800.0

[3] >>> scipy.special.factorial(10.5)

11899423.08396225

[4] >>> scipy.special.factorial(11)

39916800.0

[5] >>> scipy.special.factorial(100)

9.332621544394415e+157

[6] >>> scipy.special.factorial(1000)

inf

[7] >>> scipy.special.factorial(100) - scipy.special.factorial(100) + 1

1.0

[8] >>> scipy.special.factorial(100) - (scipy.special.factorial(100) - 1)

0.0

There’s a few things to learn here. Note that the return type of scipy.special.factorial() is a float.

You might also be surprised to find that the function gives a return value for 10.5, and that’s because the function actually has codes to calculate the “gamma function”, a continuous function whose values for integer arguments are given by \( \Gamma(n) = (n-1)! \) .

For an input value of 1000, the result is too large for the float variable type, so inf is returned instead.

Also, notice the weird behavior of lines [7] and [8]: mathematically we know that \( 100! - 100! + 1 = 1\) and it shouldn’t matter how we group the operations, but in Python the result is either 1.0 or 0.0 depending on the order of operations.

In line [7], the expression is evaluated from left to right, so the result of scipy.special.factorial(100) - scipy.special.factorial(100) results in 0, followed by adding 1.

In line [8], the parentheses forces (scipy.special.factorial(100) - 1) to be evaluated first, but due to the finite precision of floating point numbers (Python floats have 64 bits, corresponding to about 16 significant figures), subtracting 1 from 9.332621544394415e+157 does not change the result at all.

Although these issues do not always come up in practice, they can seriously throw you off when they do, so it is always a good idea to keep the finite precision of floating point numbers in mind.

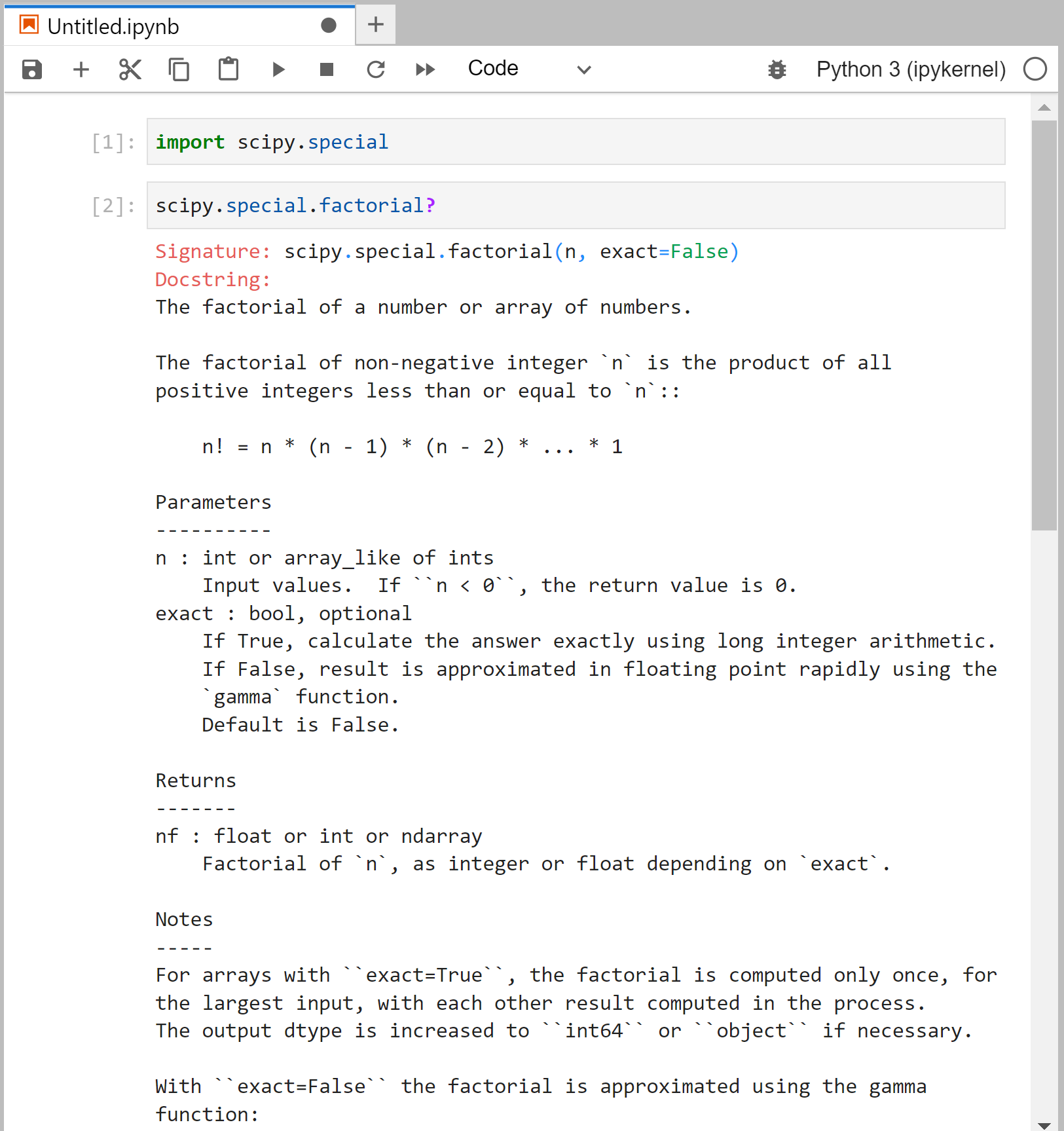

When you’re not sure how to use a function in terms of its arguments and/or return values, you can check the function’s documentation.

You can easily do this in the Jupyter notebook by passing the function name into help() or by appending a question mark:

As you can see from the screenshot, the documentation tells you a great deal about the different ways the function can be called; one important detail is that it also accepts array inputs, which is very common in NumPy and SciPy.

Although the documentation does not directly affect how the code runs, it can be just as important for the user as the code itself, so make sure you also write quality documentation!

Note: Adding a # in Python makes everything on the line following it into a comment. Enclosing text between a pair of triple quotes """ creates a docstring, which is also how functions are documented.

You can define your own functions in text files and notebooks as well. The syntax for a function is summarized in the following:

def calculate_interest(principal, interest_rate, days=365):

""" Calculate the interest on a loan compounded daily.

Parameters

----------

principal : float

The amount of money borrowed.

interest_rate : float

The interest rate, expressed as a percentage (i.e. 3.5% should be entered as 3.5)

days : float

The number of days the loan is held.

Returns

-------

interest : float

The amount of interest on the loan.

"""

daily_rate = interest_rate/100/365

factor = (1 + daily_rate)**days

interest = (factor*principal) - principal

return interest

The first line starting with def names the function (calculate_interest) and specifies the arguments (principal, interest_rate, days).

The arguments are the inputs to the function and determine the variable names in the function body.

The docstring (between the triple quotes) is the documentation that explains how the function is used.

The code in the function body is indented from the function definition: this is an essential portion of the Python syntax that determines whether your code is inside of a “block” or outside.

Finally, the return value can be assigned to a variable if you call a function as interest = calculate_interest(1000, 22.99, days=180). (This is an example that shows how much interest you owe with a $1,000 balance on a credit card with a 22.99% interest rate for 180 days).

Note that principal and interest rate are required arguments to the function, whereas days is called a keyword argument.

Keyword arguments have default values that are used if not provided in the function call.

Note: A function defined in a module can be imported into a script, module, or notebook.

Note 2: The scope is the region of code where a variable is available. The concept of scope is very important. The variable names principal, interest, days, daily_rate, factor are only available from inside the function calculate_interest. If you try to print(daily_rate) outside of the function, you will encounter a NameError: name 'daily_rate' is not defined. However, you may define a variable with the same name outside the function. Variables defined outside of functions have global scope, and can be accessed from inside the function and outside. However, if a variable is both locally and globally defined, the local definition takes priority.

The context of (), [], and {}

One potentially challenging aspect of programming is that simple structures such as words, parentheses, and brackets have different meanings depending on where in the code they are used.

For this reason, it’s worthwhile to have a special section that talks about the multiple meanings of parentheses (), square brackets [], and curly braces {}.

- Parentheses

()- Calling a function or method. Used when parentheses come after a name, such as

main(),range(5)ormy_string.capitalize(). Often these calls return a value that can be assigned to a variable using=, such asfive = int("5"). Empty parentheses refer to functions and methods that are called without arguments. - Specifying order of operations. Used when combined with operators, such as

answer = (2*3) + 5 - Creating a tuple. For example,

my_tuple = (five, 6, 4+3).()that does not follow a name refers to an empty tuple. - Creating a generator. These are list-like entities whose values are not stored in memory but are generated as needed. This is relatively advanced usage and not essential right now.

- Getting around indentation rules. You can use parentheses to group together multiple lines of code as a single line.

- Calling a function or method. Used when parentheses come after a name, such as

- Square brackets

[]- Indexing a variable. Used when square brackets come after a variable name to extract an element or a range of elements, for example:

myString = "science"; letter = myString[2]. Here, the value ofletteris"i"because the element number starts from zero. If using parentheses to get an element from a list, an error will result because Python will think you are calling a function.- There are many ways to retrieve elements from a string, list, tuple, or array. For example,

"science"[0]returns the letter"s","science"[1:3]returns the letters"ci","science"[::2]returns"sine"and"science"[::-1]returns"ecneics".

- There are many ways to retrieve elements from a string, list, tuple, or array. For example,

- Looking up a value from a dictionary. See “Creating a dictionary” below.

- Creating a list. When not combined with a variable name, a list can be created using square brackets that enclose a comma-separated sequence of variables, such as

my_list = [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5].- Note that the same list can be created using

my_list = list(range(6)). (Note thatrange(6)returns a generator in Python 3.) - A list comprehension is a way to create a list in a single line of code, such as

my_list = [i*2 for i in range(6)].

- Note that the same list can be created using

- Indexing a variable. Used when square brackets come after a variable name to extract an element or a range of elements, for example:

- Curly braces

{}- Creating a set. For example,

my_set = {1, 3, 3, 4}returns a set with three unique elements1, 3, 4. In my experience, sets in Python are not commonly used and rarely created this way. - Creating a dictionary. For example,

my_dict = {"jan":"january", "feb":"february"}creates a mapping that allows values (e.g."january") to be returned bymy_dict["jan"]. The keys to the dictionary can be strings and numbers (or tuples containing these). - Note that curly braces are used in C and C++ to demarcate functions, if statements, loops etc. Remember that Python uses indentation for that.

- Creating a set. For example,

Loops and conditional statements

One of the great advantages of programming is automation, and a basic component of automation is the loop.

A for loop is a structure that iterates over a sequence and does something for each element in the sequence.

For example, you can iterate over the elements of a list, or the keys in a dictionary, or a range of numbers using the range() function.

The range(n) function provides a means to iterate from zero up to (but not including) n.

You can easily build up a list containing many elements by starting from an empty list [], then writing a for loop that appends one element to the loop per iteration.

Use indentation to separate the content of a loop from the outside.

Another useful structure is the conditional statement if ... else, which is useful for making decisions.

The basic syntax for the if statement is that the content inside the block is executed if the accompanying operator returns True.

If it returns False, then you can add elif (short for “else if”) statements that are executed if their operators return True.

The else statement catches all of the remaining cases.

Another loop structure is the while loop, which iterates as long as the accompanying operator returns True.

“While” very useful, it is easy to write incorrect code that results in the while loop iterating forever so it’s important to be careful.

myStuff = [] # Initialize an empty list

for i in range(5): # Iterate 0, 1, 2, 3, 4

if i%2 == 0: # Check if i is an even number

myStuff.append(str(i) + " is even")

elif i%3 == 0:

myStuff.append(str(i) + " is odd and a multiple of 3")

else:

myStuff.append(str(i) + " is odd and not a multiple of 3")

print(myStuff)

> ['0 is even', '1 is odd and not a multiple of 3', '2 is even', '3 is odd and a multiple of 3', '4 is even']

Methods of objects and variables

The word method has a very specific meaning in Python, and that is a function belonging to an object. In Python, every variable is an object, which means it possesses methods. This makes the most sense with some examples. Take for example string variables - when working with strings, you might be interested in separating a long string into substrings using a specified character as a delimiter:

myStr = 'The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog'

myStr.split()

> ['The', 'quick', 'brown', 'fox', 'jumped', 'over', 'the', 'lazy', 'dog']

'To be, or not to be, that is the question'.split(',')

> ['To be', ' or not to be', ' that is the question']

Here are two examples of the split() method. (It is customary when referring to functions and methods to put () after the name.)

As you can see, the default delimiter is the space character, but you can also specify other delimiters such as ",".

In the latter case, two of the substrings contain leading spaces.

Leading and trailing spaces, and other “invisible” characters can be removed from a string using the strip() method.

Strings are “immutable” and their values cannot be changed, so these methods return a different variable rather than changing the string content in-place.

A list has a method called index(). It returns the position of an element in a list, and can be used in the following way:

myStr = 'The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog'

splitted = myStr.split()

print(splitted.index('over'))

> 5

print(splitted.index('cat'))

> ValueError: 'cat' is not in list

More broadly, every variable in Python, from integers to floats to strings to functions, is an object.

An object is constructed from a class, a structure which defines the methods and attributes of the object.

For example, str is a class and "To be or not to be" is a string object, or an instance of the str class.

The relationship between a class and an object is similar to the relationship between an abstract concept, and something that exists in the real world (for example, the class is the idea of a book as something that has covers, pages, and text, and objects are the physical books on your bookshelf or in your library).

In object-oriented programming, the class is the code that defines how objects are created.

Reading and writing from files

Working with files is universal to programming, because files are how data is stored in the long term. Files come in a variety of formats, such as .doc and .mp4 and .jpg, which hold different kinds of data, structured according to a standard, so that they can be read from and written to by programs. At a lower level, all files are stored as bits (zeros and ones), and we often say they are stored in bytes (8 bits). Different types of files differ greatly in how they use the bytes to store data. If the bytes are used to represent text in a standard way, such as ASCII or UTF-8, then the file is said to be a text file. Many other types of files do not use bytes to represent text, and are called binary files. If you use a text editor to open these, they appear as gibberish.

More generally, a file can only be understood by a program that knows how it is organized. Groups of people publish standards that dictate what the organization of a file should be, and it’s up to the programmers to follow this standard to varying degrees (for example, Adobe Photoshop and Mac OS’s Preview both need to follow the JPEG standard, which is published by the International Standard Organization (ISO)). So the world really does have a need for control freaks. 😉 (By the way, the UTF-8 standard is how we can have emojis as characters in text files, rather than storing them as pictures. When the text editor or web browser reads the text file, it knows that the emoji character should be shown as a picture. And that’s why they show up differently on different operating systems as well.)

A text file could be thought of as a list of lines, and each line is a string that contains words together with spaces, punctuation, etc. An easy way to read the file - though not the only way - is to create the list of lines as follows:

lines = open("my_file.txt").readlines()

In a single line, the open() function creates a file object from the provided file name, and then the readlines() method creates a list of lines from the file contents.

This is the easiest way to work with text files that aren’t too large (i.e. a novel is fine, but maybe not the contents of the Shields Library).

Note: The file extension does not have to be .txt; it could be .out, .dat, or anything you choose.

Files don’t need to have extensions in order to be valid.

However, operating systems use the file extension as a hint to what the files contain, and to determine the default program for opening the file, so it’s a bit confusing to set the file extension of a text file to .jpg or .mp3.

Each string in lines has the content of one line in the text file.

You could further split the string into substrings (corresponding to words) and operate on the individual words.

This could be very useful in automating tasks because other programs will typically produce their output as files.

For example, if I know that the energy output in a Psi4 Hartree-Fock calculation is always printed in the following way:

@DF-RHF Final Energy: -412.51505740373381

I could then look for the string "DF-RHF Final Energy" in each line, and if there is a match, then I split the string and convert the last word to a float.

This could be convenient if I was trying to extract the energy from a large number of Psi4 calculations.

To write a text file, there is a corresponding way to write a list of lines. However, the file must be explicitly opened in write mode (which will overwrite any existing content) or append mode (which will add content to the end). A simple example of writing a file would be like this:

out_data = ["Hello there", "Nice weather we're having"]

out_file = open("my_output.txt", "w")

out_file.writelines(out_data)

out_file.close()

Note that the file object out_file must be closed after the lines are written. Otherwise, the data might not actually be written to the file, the operating system might not be able to rename or move the file, or other “file open”-related issues could occur.

It is possible to accidentally leave a file open. In Python, the with statement allows you to work with an open file inside a block as follows:

out_data = ["Hello there", "Nice weather we're having"]

with open("my_output.txt", "w") as out_file:

out_file.writelines(out_data)

Using with statements is preferable because the file is automatically closed when the program exits the block.

Formatting strings

You will often be interested in printing strings that contain data from your variables.

Python provides many ways to convert variable values into strings, and the recommended way of doing this in Python 3 is using “f-strings”.

This is achieved by adding f directly in front of the string, and putting curly braces around the variable names to be substituted into the string.

An example is here:

with open("square_roots.txt", "w") as out_file:

for i in range(10):

sqrt_i = i**0.5

out_str = f"The square root of {i} is {sqrt_i}"

print(out_str, file=out_file)

Note 1: Note that we used the file= keyword argument of the print() function that causes the printed text to be written to the file instead of the notebook output.

Note 2: The print() function supports variable numbers of arguments, so we could have done the same thing with print("The square root of", i, "is", sqrt_i, file=out_file), but that is still limited compared to learning string formatting, as you will soon see.

The file “square_roots.txt” will be located in the same folder as your notebook file and contain the contents:

The square root of 0 is 0.0

The square root of 1 is 1.0

The square root of 2 is 1.4142135623730951

The square root of 3 is 1.7320508075688772

The square root of 4 is 2.0

The square root of 5 is 2.23606797749979

The square root of 6 is 2.449489742783178

The square root of 7 is 2.6457513110645907

The square root of 8 is 2.8284271247461903

The square root of 9 is 3.0

You may want to further customize the format of your string, such as controlling the number of digits being printed out, or using scientific notation, etc. This is also achievable using f-strings, for example:

with open("square_roots.txt", "w") as out_file:

for i in range(20, 140, 20):

sqrt_i = i**0.5

out_str = f"The square root of {i:3d} is {sqrt_i:9.3f}"

print(out_str, file=out_file)

Note: We changed the values in the range by providing the starting and ending values as well as the spacing. The range() function does not include the ending value by design.

This time the content of your file will be:

The square root of 20 is 4.472

The square root of 40 is 6.325

The square root of 60 is 7.746

The square root of 80 is 8.944

The square root of 100 is 10.000

The square root of 120 is 10.954

See how the columns are nice and clean? This is important when you want another program to read your output file, or when working with experimental data and you don’t want to print non-significant digits.

The special codes {i:3d} and {sqrt_i:9.3f} mean that the variables i should be printed as a base-10 integer with width 3, and sqrt_i as a float with width 9 and 3 digits after the decimal. The special codes for string formatting are shared across different programming languages and you can look them up here: C++ printf reference. I’ve used this page since 2006!