Week 6: Chemical Kinetics and Numerical Integration

Overview and Objectives

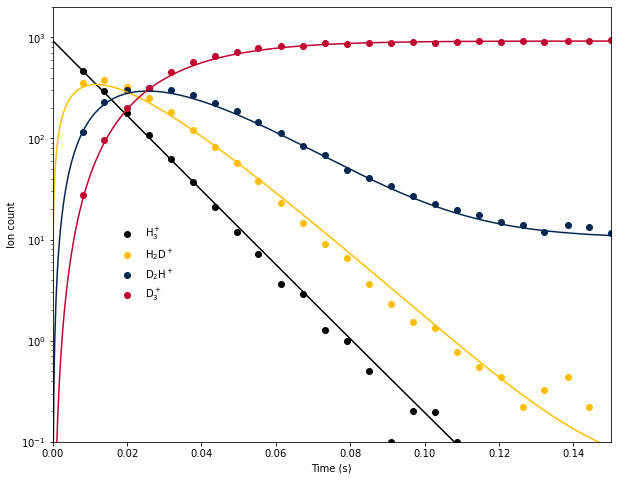

Last week we used a system of integrated rate equations to model the time evolution of H\(_3^+\) and its deuterated isotopologues in an ion trap at 13.5 K, based on data from E. Hugo et al. (2009) J. Chem. Phys. 130, 164302. This approach suffered from a few serious limitations:

- When two or more of the rate constants were equal, the rate equation broke down because of division by 0 and an alternate form had to be derived.

- The rate equations assumed that [HD] was constant, and that all of the reverse reactions were negligible. Relaxing either assumption would require rederiving the rate equations, which may not even be possible in a closed form.

- The agreement of the model with the experimental data was adequate, but at long times the qualitative shape was incorrect, indicating that one or more processes were missing from the model.

These limitations motivate an alternative approach to solving for concentrations/abundances as a function of time. In fact, models of most “real” chemical systems (e.g., atmospheric chemistry, marine chemistry, combustion, etc.) involve tens or hundreds of molecules linked by hundreds or thousands of elementary reactions, making the integrated rate approach impossible. General chemical kinetics models can be made by numerically integrating the coupled differential rate equations, and that is the subject of this week’s notebook.

Background

H\(_3^+\) Deuteration

Last week, we considered the following system of reactions under pseudo-first-order conditions (i.e., [HD] was constant):

| Reaction | Rate (cm\(^{-3}\) s\(^{-1}\)) |

|---|---|

| H\(_3^+\) + HD \(\to\) H\(_2\)D\(^+\) + H\(_2\) | \(k_1\)[H\(_3^+\)][HD] |

| H\(_2\)D\(^+\) + HD \(\to\) D\(_2\)H\(^+\) + H\(_2\) | \(k_2\)[H\(_2\)D\(^+\)][HD] |

| D\(_2\)H\(^+\) + HD \(\to\) D\(_3^+\) + H\(_2\) | \(k_3\)[D\(_2\)H\(^+\)][HD] |

Because the temperature was low, we ignored the reverse reactions. However, it turns out that ignoring the reverse reactions is not a good assumption! There are 2 reasons for this:

- Experimentally, the HD has only has a purity of 97%. The other 3% is a mixture of H\(_2\) and D\(_2\), and H\(_2\) is a reactant for the reverse reaction.

- Despite how strongly exothermic these reactions initially appear, H\(_2\) is a special molecule. It has two nuclear spin modifications called ortho-H\(_2\) and para-H\(_2\) that behave like different molecules, and “normal” hydrogen is 75% ortho and 25% para. Ortho hydrogen has the equivalent of 170 K more internal energy than para hydrogen, and this extra energy makes the reverse reactions feasible even at very low temperatures. If we try to include the reverse reactions into our rate equations, we will very quickly run into major headaches trying to analytically integrate them. However, they present no challenge for numerical integration! We can also explicitly model the concentrations of H\(_2\) and HD over time in case our assumption that they are constant is not good. Our new second-order rate equations become:

| Reaction | Forward Rate (cm\(^{-3}\) s\(^{-1}\)) | Reverse Rate (cm\(^{-3}\) s\(^{-1}\)) |

|---|---|---|

| H\(_3^+\) + HD \(\rightleftharpoons\) H\(_2\)D\(^+\) + H\(_2\) | \(k_1\)[H\(_3^+\)][HD] | \(k_{-1}\)[H\(_2\)D\(^+\)][H\(_2\)] |

| H\(_2\)D\(^+\) + HD \(\rightleftharpoons\) D\(_2\)H\(^+\) + H\(_2\) | \(k_2\)[H\(_2\)D\(^+\)][HD] | \(k_{-2}\)[D\(_2\)H\(^+\)][H\(_2\)] |

| D\(_2\)H\(^+\) + HD \(\rightleftharpoons\) D\(_3^+\) + H\(_2\) | \(k_3\)[D\(_2\)H\(^+\)][HD] | \(k_{-3}\)[D\(_3^+\)][H\(_2\)] |

\[ \frac{\text{d}[\text{H}_3^+]}{\text{d}t} = -k_1[\text{H}_3^+][\text{HD}] + k_{-1} [\text{H}_2\text{D}^+][\text{H}_2] \]

\[ \frac{\text{d}[\text{H}_2\text{D}^+]}{\text{d}t} = k_1[\text{H}_3^+][\text{HD}] + k_{-2}[\text{D}_2\text{H}^+][\text{H}_2] - k_2[\text{H}_2\text{D}^+][\text{HD}] - k_{-1} [\text{H}_2\text{D}^+][\text{H}_2]\]

\[ \frac{\text{d}[\text{D}_2\text{H}^+]}{\text{d}t} = k_2[\text{H}_2\text{D}^+][\text{HD}] + k_{-3}[\text{D}_3^+][\text{H}_2] - k_{-2}[\text{D}_2\text{H}^+][\text{H}_2] - k_3[\text{D}_2\text{H}^+][\text{HD}]\]

\[ \frac{\text{d}[\text{D}_3^+]}{\text{d}t} = k_3[\text{D}_2\text{H}^+] [\text{HD}]- k_{-3}[\text{D}_3^+][\text{H}_2]\]

\[ \frac{\text{d}[\text{H}_2]}{\text{d}t} = k_1[\text{H}_3^+][\text{HD}] + k_2[\text{H}_2\text{D}^+][\text{HD}] + k_3[\text{D}_2\text{H}^+][\text{HD}] \\ - k_{-1} [\text{H}_2\text{D}^+][\text{H}_2] - k_{-2}[\text{D}_2\text{H}^+][\text{H}_2] - k_{-3}[\text{D}_3^+][\text{H}_2] \]

\[ \frac{\text{d}[\text{HD}]}{\text{d}t} = k_{-1} [\text{H}_2\text{D}^+][\text{H}_2] + k_{-2}[\text{D}_2\text{H}^+][\text{H}_2] + k_{-3}[\text{D}_3^+][\text{H}_2] \\ - k_1[\text{H}_3^+][\text{HD}] - k_2[\text{H}_2\text{D}^+][\text{HD}] - k_3[\text{D}_2\text{H}^+][\text{HD}] \]

Since we know the abundances of all 6 species at the beginning of the experiment, we can numerically integrate this system of equations to compute their abundances as a function of time. This is an example of an initial value problem: we know the initial values of the abundances and their rates of change, and we want to know the abundances at a later time.

Basic Numerical Integration: Forward Euler Method

The Forward Euler Method is the simplest algorithm for numerically integrating differential equations. To keep things simple, we’ll use a 1D function as an example, but the same concepts apply to multidimensional ones as well. Recall that the derivative of a function \(f^\prime(t)\) is equal to the slope of the function’s tangent line: d\(f\)/d\(t\). If we know the value of the function at one point \(f(t)\), we can take a small time step \(\Delta t\). The derivative then approximately becomes:

\[ f^\prime(t) \approx \frac{\Delta f}{\Delta t} = \frac{f(t+\Delta t) - f(t)}{\Delta t} \]

and so we can rearrange to get

\[ f(t+\Delta t) \approx f(t) + f^\prime(t)\,\Delta t \]

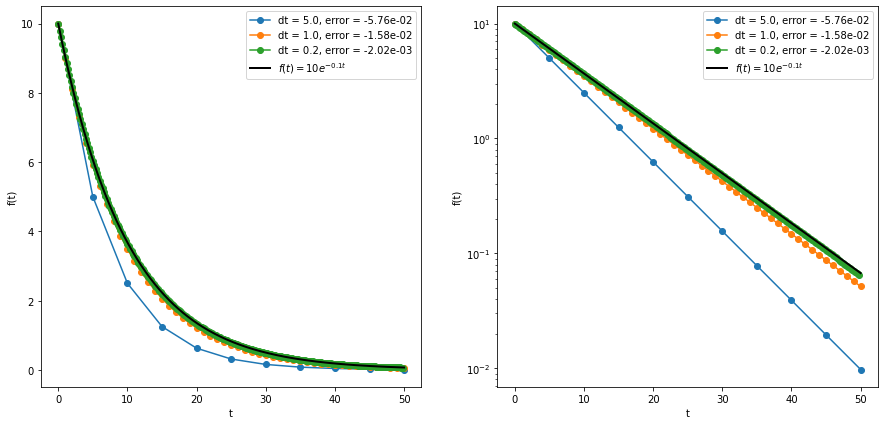

This formula becomes exact as \(\Delta t \to 0\), but practically \(\Delta t\) is always a (small) nonzero number. We can then repeat this process for as many time steps as needed to reach our target final time. But, since the Euler method is approximate, there may be some error associated with each step (the local truncation error). For the simple Euler method, the local truncation error scales with \((\Delta t)^2\) as long as the step size is small. The global truncation error is just the sum of all of the local truncation errors at each step. Since the number of steps taken is equal to \((t_f-t_0)/\Delta t\), the global truncation error is proportional to \((\Delta t)^2/(\Delta t) = (\Delta t)^1\). So in total we expect the error to be proportional to the step size raised to the first power, and the forward Euler method is considered a first-order method. Other methods exist whose errors are proportional to higher powers of \(\Delta t\), which is more desirable since a small reduction in step size leads to a big reduction in the error. An example of the forward Euler method applied to the function \(f(t) = 10e^{-0.1t}\) is shown in the figure below, and the code is in the euler.ipynb file linked below.

For our chemical kinetics problem, we can simply represent the concentrations as an array, and the forward Euler method becomes

\[ \begin{bmatrix} n_1 \\ n_2 \\ \vdots \\ n_N \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \text{d}n_1/\text{d}t \\ \text{d}n_2/\text{d}t \\ \vdots \\ \text{d}n_N/\text{d}t \end{bmatrix}\Delta t \]

In our case, we have 6 molecules, and each molecule has a corresponding rate equation, so \(N=6\) and the derivatives are given by the equations above.

Higher-Order Methods

Scipy of course has more sophisticated numerical integration algorithms available for use; these can be found in the scipy.integrate module. Specifically, for our purpose the scipy.integrate.solve_ivp function allows for solving these initial value problems using your choice of integration method and a bunch of extra features, some of which we will explore in the ode.ipynb notebook. The most commonly-used higher order routine is the fourth-order Runge-Kutta method (RK4). Here we’ll briefly outline the algorithm as applied to our specific problem of chemical kinetics (see the further reading materials for a more complete discussion). To keep things simple, we will write the algorithm for one molecule, but it can be easily extended like before by using an array of molecules instead of a single value. Our initial value problem is:

\[ \left.\frac{\text{d}n_i}{\text{d}t}\right|_{t_i} = f(n_i), \quad n_0 \equiv n(t = t_0) \]

Here, \(n_i\) represents the abundance of the molecule at time \(t_i\), and we know its value \(n_0\) at \(t_0\). Its derivative is a function of its abundance \(f(n_i)\) but otherwise does not explicitly depend on time, so this is considered a time-invariant system. Given a step size \(\Delta t\), the RK4 method is:

\[ n_{i+1} = n_i + \frac{1}{6}(K_1 + 2K_2 + 2K_3 + K_4)\Delta t \\[1em] t_{i+1} = t_i + \Delta t \]

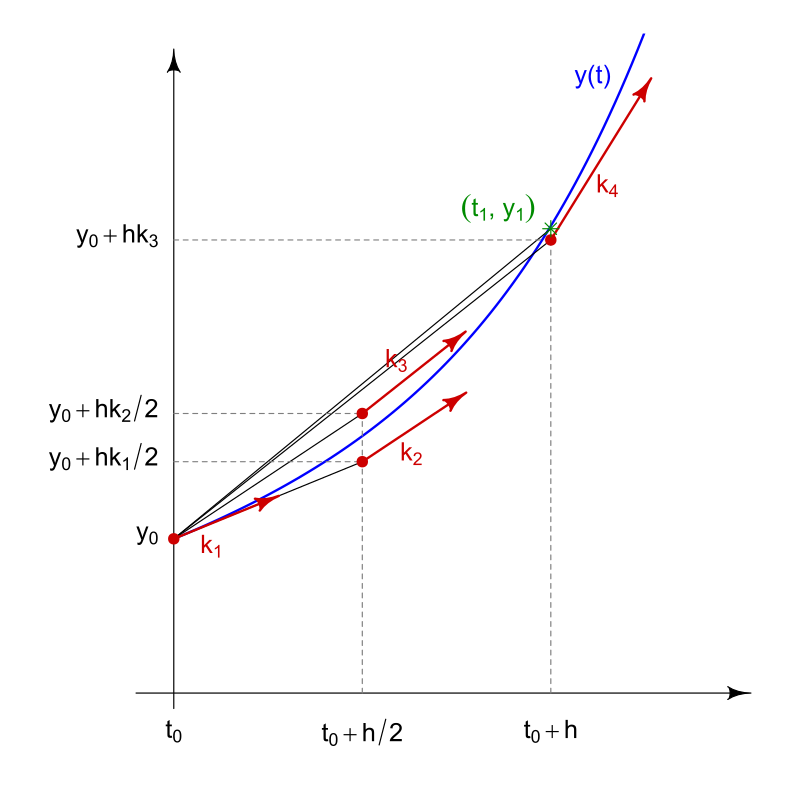

In this equation, the \(K\) values are different estimates of the derivative, and the formula uses a weighted average of these estimates to calculate the actual change in abundance. The \(K\) values are calculated as:

\[ K_1 = f(n_i) \\[1em] K_2 = f(n_i + \frac{K_1}{2}\Delta t) \\[1em] K_3 = f(n_i + \frac{K_2}{2}\Delta t) \\[1em] K_4 = f(n_i + K_3\Delta t) \]

In these equations, \(K_1\) is the estimate of the slope from the Euler method. \(K_2\) is an estimate of the slope at the midpoint of the step size. \(K_3\) is a different estimate of the slope at the midpoint, but is calculated using the slope from \(K_2\) instead of \(K_1\). Finally, \(K_4\) is an estimate of the slope at the end of the step. The figure below from Wikipedia attempts to illustrate the process, though the notation is slightly different.

Fortunately, this and other algorithms are included in Scipy, so there is no need to code them by hand. This week we will use the RK4 method to numerically integrate the system of equations for the H\(_3^+\) deuteration experiment and see if we can improve agreement with the experimental data by including the reverse reactions.